The Washington State Training School for Girls near Grand Mound, later renamed Maple Lane School, was originally a place for girls who were deemed troubled or delinquent. For over 100 years, the facility has played a role in the community, and for the state at large, in employment, education and rehabilitation.

The first girls arrived by train from the crowded and co-ed Washington State Reform School in Chehalis, known as Green Hill School today. The new girls’ facility was funded from a recently passed appropriations bill. The Grand Mound, 160-acre site, just south of today’s Highway 6, was selected and officially opened December 22, 1914. The cottages, named Hawthorn and Spruce, were each self-contained, including sleeping quarters for the girls. Subsequent cottages were added in later years. Birch Cottage, a special rehabilitation facility within the larger school, was for girls who had more severe challenges and struggles. They required more attention than could be given while among the general population.

Philosophical Approach

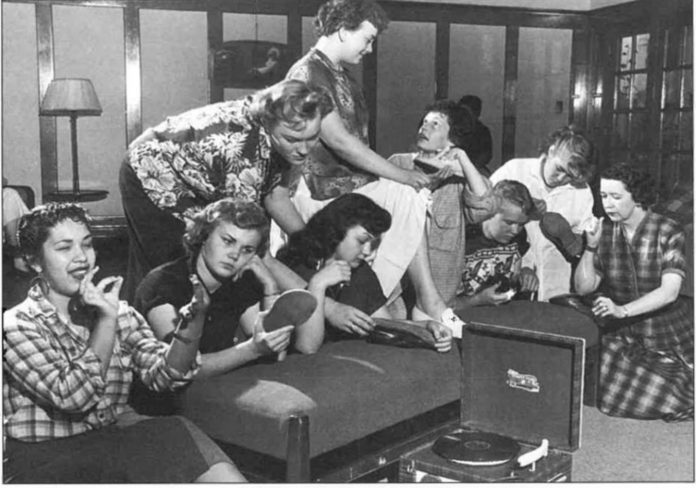

The 1950s and 1960s brought changes in practices. The focus moved from punishment to help. Boys were brought over daily from the Cedar Creek Youth Camp for classes. Exactly who could be detained shifted when the state legislature changed the law in 1967. No longer could abuse, neglect or abandonment result in institutionalization, and that went on to later include youth who were truant, runaway or deemed ungovernable.

Key philosophical ideas were required of teachers and staff. They were to be active communicators amongst each other about how each girl was progressing. They must be careful not to set standards so high that the girls could not achieve them and therefore feel repeated failure. Their students were in need of positive rewards and positive attitudes from their teachers. Classes were small, about 15 girls, and each was approached based on her needs. “We teach the students,” said staff member C.J. Irey in a 1967 interview, “not the subjects.”

Group life counselors took the lead on rehabilitation with a four-part approach. They were tasked with protecting society from the girl and the girl from society, to know her whereabouts at all times and provide attainable routines and protocols. Girls were taught how to organize their everyday lives; have appropriate, balanced relationships with other; and given a sense of belonging.

Opportunities for Growth

Workshops and celebrations supplemented education. College and university consultants were invited. A pre-vocational beauty school course was offered. In addition to full business operations, the students honed their relationship skills and built confidence in a real-world situation. A Title 1 funded pre-school pilot program was introduced in 1970, created by the University of Washington Experimental Education Unit of the Child Development Center. Caring for preschoolers gave uplifting experience and helped build self-worth and confidence. For those completing the program, there was job placement assistance. In the first ever release program from Maple Lane, girls took paid positions as pages in the Washington State House of Representatives. After 1981, Maple Lane became a boys-only facility, and the girls were transferred to Echo Glen Children’s Center in North Bend. The home economics courses were discontinued and replaced with an agriculture business class. In later years, a culinary and art program were added.

Culture Honored

In the early 1970s, Young Gifted and Black, a special services group for Black girls at Maple Lane, had a goal to help improve girls’ self-image. 185 people attended their program for Black History Week. A salmon bake and fashion show were presented by the school’s Native group, who met weekly learning crafts and traditions to help them identify with their Native community after leaving Maple Lane. The Seattle Indian Center Youth Program came and modeled traditional and contemporary clothing.

Saint Martin’s College Drama Club put on a three-act comedy of “Oh Men! Oh Women!” and the “It’s Okay to be a Woman” workshop focused on topics such as assertive, passive and aggressive behavior and hosted presenters from regional social services and a female state patrol trooper.

Community Workforce

Maple Lane was a longtime career for many people in the surrounding area. Counselors, teachers, kitchen staff, maintenance and all the administrative and support staffing that goes with both a school and a secured facility. However, state budget cuts continued to loom. After the early 2000s, the debate ran about which facility to close, Maple Lane among others, how many jobs would transfer and how many would be eliminated. Running concerns simultaneously cited insufficient funding and insufficient space for more offenders. By the mid 2000s, it was scheduled for removal from the state’s juvenile rehabilitation program, and a phasing out to closure plan was in place. Employment numbers ran from 256 to 260 people, and they were all concerned about the future of their jobs. Some staff transferred to Green Hill School, as did some of the inmates.

Maple Lane closed in 2011 and was reopened in 2016 for an adult population with unique needs, such as male offenders who had mental health or cognitive functioning issues and were not prepared to stand trial. Prior, they were waiting in jail or the state hospital, so the Washington State Department of Social and Health Services renovated the building for the purpose of restoring the competency of 30 adult patients. The facility’s latest attention was in 2020 when it was proposed as a COVID-19 isolation and quarantine site.